IWC Schaffhausen

Special Service: The IWC Porsche Design Ref. 3519 AMAG

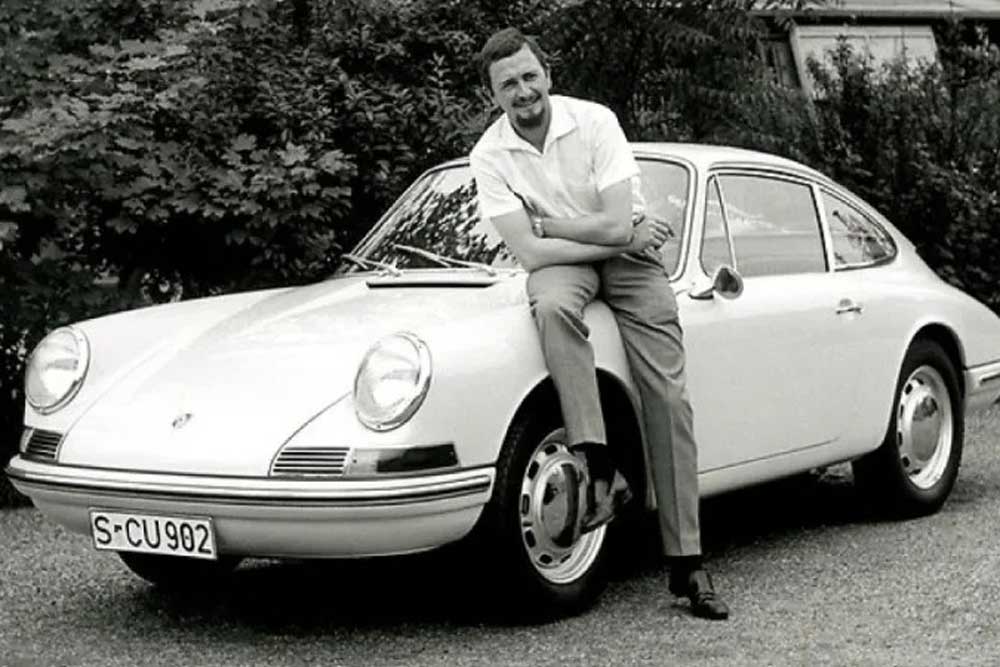

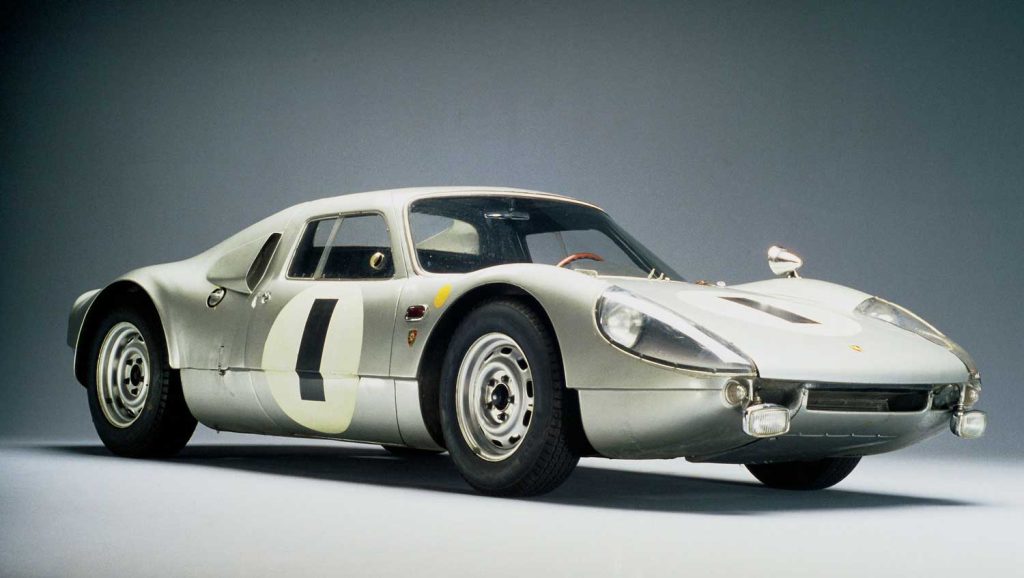

When Professor Porsche died in 1951, the ownership of his eponymous firm was shared between his two children: Ferdinand (known as Ferry) and Louise, who was married to one of Professor Porsche’s colleagues, Anton Piech. Soon a rift appeared between Ferry and Piech and trouble bubbled under the surface for two decades until, in 1972, the management decided that no member of the Porsche/Piech families could be involved in the running of the firm. This devastated Ferry, as it meant that his son, Ferdinand (nicknamed “Butzi”) who, as head of design, had overseen the introduction of the 904 race car and the 911 road car, now had to leave.

Ferdinand Alexander 'Butzi' Porsche, designer of the Porsche 911

Porsche 904 Carrera GTS, 1964 (Image: Porsche AG)

Orfina chronograph ref. 7176S by Porsche Design, circa 1970s (Image: Christie’s)

IWC Porsche Design compass watch ref. 3510

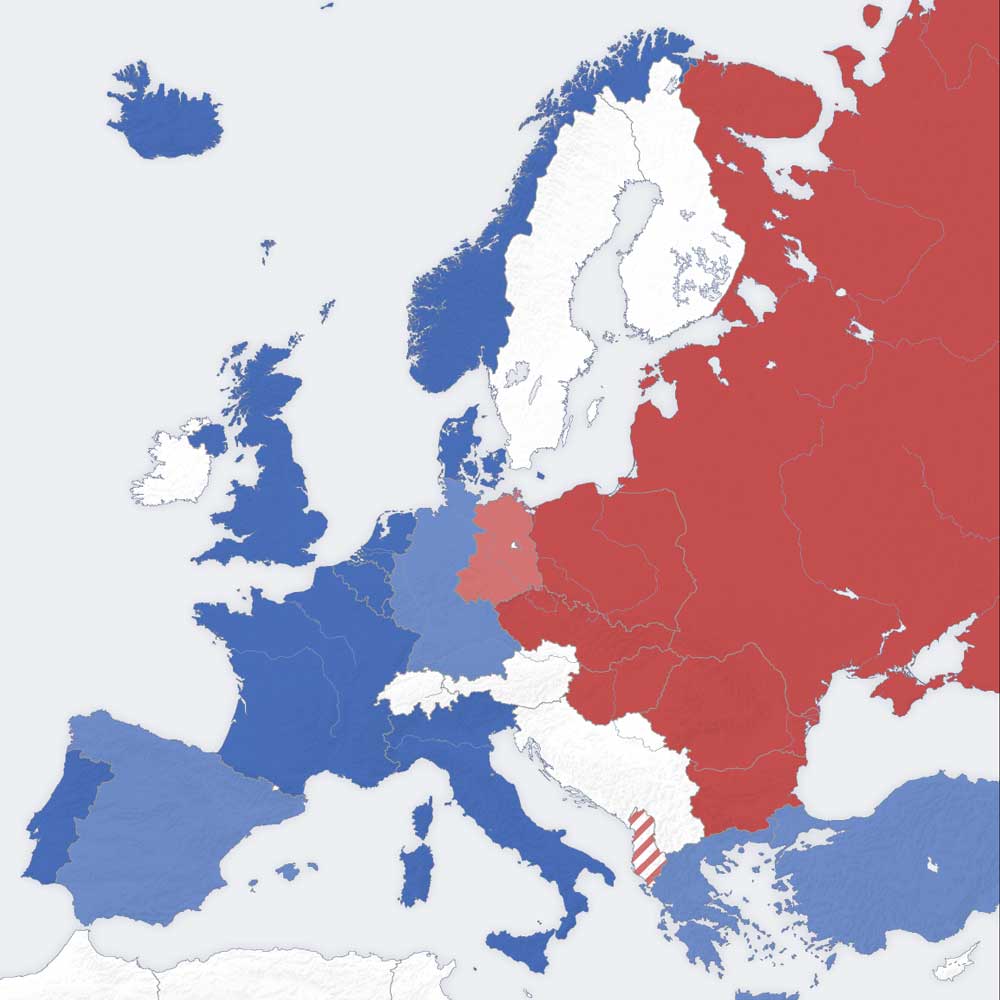

<h2?Red Alert

Whilst this was happening in Switzerland, over the border in Germany the focus wasn’t on watches but on the building Soviet threat. At the end of the 1970s, the Cold War seemed in danger of becoming hot: the Soviets had invaded Afghanistan and began to install SS20 missiles targeting NATO’s European bases; the US was planning on installing cruise missiles at bases throughout Europe; and the US attempt to rescue the hostages held in Tehran had ended in failure. Both sides in the Cold War knew that if war ever came, it would mostly be fought in Germany, where the NATO allies of France, the UK and the US had vast armies stationed and the armed forces of the federal German Republic (Bundeswehr) were the largest in Western Europe, with almost half-a-million men ready for combat.

Cold War map of central Europe, NATO (blue) against the Warsaw Pact (red)

To aid them in this task the German Navy trained three different types of diver according to their military task. There are Waffentaucher (weapons diver), Kampfschwimmer (combat swimmer) and Minentaucher (mine clearance diver).

Combat swimmers

Combat swimmers

Non-Magnetic Requirements

As the Soviets made the best anti-shipping mines in the world, they wished to keep their technology secret, so the mines were fitted with anti-handling devices, designed to explode the mine if any attempt was made to defuse it. These anti-handling devices often used magnetic triggering for their mines, meaning that any mine-clearance diver had to be equipped entirely with non-magnetic equipment.

The requirement issued by the Bundeswehr in 1980 for a new diver’s watch was 30 pages long and asked for capabilities never previously seen in a wristwatch; it was sent to all companies with whom the Bundeswehr were currently dealing. One of the recipients was a company called Diehl Avionics, a subsidiary of the famed German instrument maker VDO who made and maintained aircraft instruments for the Luftwaffe. VDO, at that time, also owned IWC, whose new president, Günter Blümlein, had just joined IWC from Diehl, so the requirement was passed along to IWC.

At the same time as the Bundeswehr was looking for a new diver’s watch, IWC was deepening its relationship with Porsche Design and Butzi Porsche. After the successes of the Compass Watch and the Titan chronograph, Butzi Porsche was designing a diver’s watch for IWC when the Bundeswehr specification landed on his desk, so the military version and the civil one were designed simultaneously.

IWC Porsche Design Ref. 3519 AMAG (Image: Yarek Baranik of The Watch Club)

Material Solutions

IWC’s great advantage was its experience in working with titanium. This gave them a head start, but making a movement completely amagnetic is a much harder task, and the technical director of the company, Jürgen King, was given that responsibility. The first thing he did was to remove the steel ball bearings on which the winding rotor revolved, replacing them with jeweled bearings. Much more difficult was to find replacements for the steel components in the balance and escapement – the balance staff, pallet fork and hairspring.

The hairspring was replaced by one made from a niobium-zirconium alloy (the only other use for either of these metals is in constructing nuclear reactors). The steel in the balance staff and the pallet fork was replaced by items made from beryllium metal, which, although harder than steel, is also much more brittle and, due to its hardness, causes more wear and tear on the parts of the watch it comes in contact with.

As well as being tested for their depth rating, as with all the Ocean 2000 Bund watches, the 3519 AMAG watches also needed testing for their amagnetic properties. It proved impossible to do this at Schaffhausen, as the presence of so much ferrous metal in the building (probably all the machine tools) affected the magnetic field in the area. So whenever a batch of 3519 AMAGs needed to be tested, Jürgen King and a naval officer would travel to King’s home in the country where they were free from all external influences and the testing could proceed virtually unaffected.

The 3519 AMAG is the world’s first (and so far only) completely amagnetic diver’s watch and certainly one of the rarest diver’s watches ever made – in the period between 1984 and 1990 less than 50 examples were created and only a handful have ever left the inventory of the Bundeswehr. It was the last true military diver’s watch built to a government specification. Nowadays the navies which still use diver’s watches buy off-the-shelf production models, often not even bothering to engrave issue numbers on the casebacks. All of the above makes the IWC Bund, and 3519 AMAG in particular, very, very special.